This briefing paper has been compiled using information included in the Out of the Shadows Index and the ECPAT Country Overview for Peru, written in collaboration with local members CHS Alternativo.

The Out of the Shadows Index, developed by the Economist Intelligence Unit, measures how nations are addressing child sexual abuse and exploitation. Data released for the first 60 countries demonstrate that governments, the private sector and civil society need to do more to protect children from sexual violence and meet the commitments they made to Target 16.2 of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The Index was calculated by assessing legislation, policies and responses by national governments. It covers critical issues that underpin child sexual exploitation and abuse, including education, reproductive health, victim support, law enforcement and risks from the online world. The Index also addresses environmental factors such as the safety and stability of a country, social protections, and whether norms permit open discussion of the issue. It also focuses on the engagement of businesses in the technology and travel/tourism sectors in fighting child sexual abuse and exploitation.

ECPAT Country Overviews comprehensively present all the existing, publicly available information, and a detailed analysis of the legal framework for the sexual exploitation of children in a country. They provide an assessment of achievements and challenges in implementation, counteractions to eliminate the sexual exploitation of children and they suggest concrete priority actions to advance the national fight against this crime.

According to ECPAT’s Terminology Guidelines, Child sexual abuse refers to sexual activities committed against children, by adults or peers and usually involves an individual or group taking advantage of an imbalance of power. Force may be used, with offenders frequently using authority, power, manipulation, or deception.

Child sexual exploitation involves the same abusive actions. However, an additional element must also be present – exchange of something (e.g., money, shelter, material goods, immaterial things like protection or a relationship), or even the mere promise of such.

Peru ranked 12th out of 60 countries scored in the Out of the Shadows Index on the country’s response to child sexual exploitation and abuse, with a score of 63.5. This ranking places it just between two other Latin American countries, namely Colombia (63.5) and Brazil (62.9).

Peru’s position on the Index can be explained by its extremely robust legal and policy framework for addressing sexual exploitation of children.

Nonetheless, action to prevent and respond to the sexual exploitation of children in Peru can still be improved. For instance, legal frameworks on child marriage and online child sexual exploitation need tightening. In practice, inadequate coordination between national and local authorities hampers the implementation of existing policies, notably because the actual resources differ between regions and municipalities. Moreover, while data is collected and made public, its limited detail or classification does not allow analysis specific to the sexual exploitation of children. Efforts are also needed to offer access to justice and tailored services to all children, including hard-to-reach groups such as Indigenous children and children trafficked for sexual purposes.

Peru has witnessed political instability in recent times – with five presidents in office since 2016. Various socio-economic factors also play a role in the context of the sexual exploitation of children in Peru, such as poverty, school drop-out, gender inequality, some of which are concurrent with geographic inequalities and disproportionately affect ethnic minorities. Indeed, economic hardship also fosters vulnerability in children tricked by offenders who lure them through fake employment offers, especially online, then force them into situations of sexual exploitation. By September 2021, Peru had one of the world’s highest COVID-19 pandemic death rates per habitant. A 2021 academic study found that 136,572 children lost a primary or secondary caregiver in Peru due to COVID-19, increasing their vulnerability to sexual exploitation potentially interwoven with economic hardship.

The country only scored 35/100 for the Index’s indicator that measures how social perceptions of violence can influence community attitudes towards sexual exploitation and abuse of children. The 2019 National Study on Social Relations found that 58.5% of Peruvians perceived violence against children as socially acceptable and 21.5% considered that it is better not to intervene in cases of child sexual abuse.

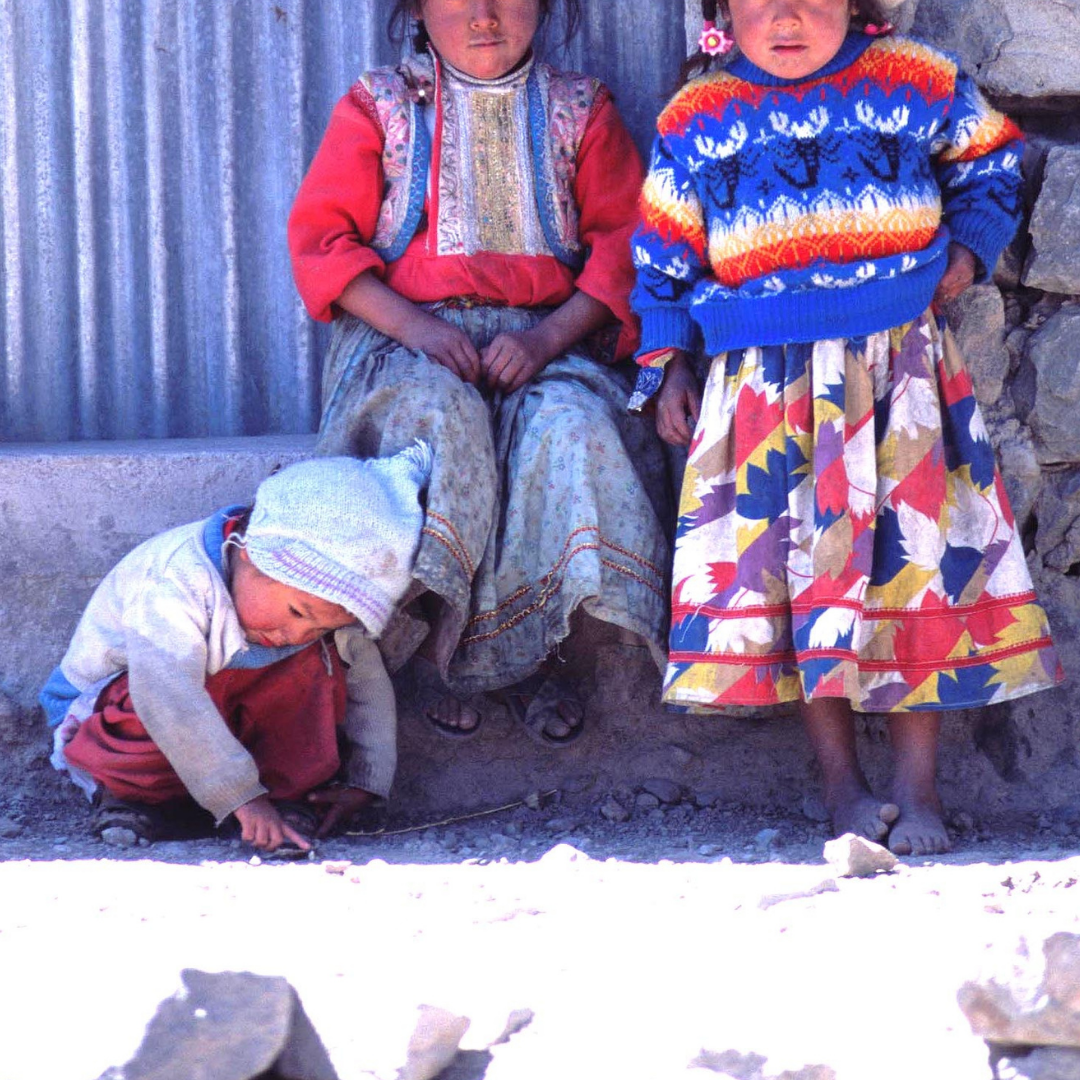

Peru is home to 55 Indigenous groups living in the Amazonian and Andean areas. Children from these communities are vulnerable to sexual exploitation due to a range of risk factors including, poverty, barriers in accessing education and isolation from services. Indigenous girls in rural areas were reported to face high risks of trafficking for sexual purposes and sexual exploitation in prostitution especially near Amazonian illegal mining sites. Moreover, research indicates that 40% of Amazonian Indigenous women from 15 to 49 were married or cohabitating before they were 18, according to the last 2017 official Census. Child marriage in Peru is sometimes tied to early pregnancies as well as traditional practices like the “Servinacuy”; a custom in some rural populations with Inca roots through which a man offers gifts to a girl’s family in exchange of living with her prior to marriage.

In 2021, the Centre for Indigenous Culture reported that Indigenous girls experiencing sexual violence faced difficulties reporting and seeking help, stating that the judiciary is ill-equipped to engage with their communities, while financial costs, travel distance and low trust in public officials discourage Indigenous people from filing criminal reports. Whilst the above report addressed all forms of sexual violence, it is likely that these barriers will exist regarding the reporting of sexual exploitation by Indigenous children.

Peru is noted as a country of source, transit and destination for child trafficking for sexual purposes. In 2020, at least 245 cases among the total 394 cases of human trafficking reported to the police were related to sexual exploitation. Of these 394 cases, 140 involved girls under 18, and 26 involved boys under 18. However, such data only covers the number of reported cases and is a fraction of the estimates of people at risk of trafficking, including for sexual purposes in Peru.

As reported by NGOs in 2021, young people, including children, and mostly girls, are trafficked into mining areas for sexual purposes. Often they are deceived with fake offers of work and then on arrival are forced into prostitution in brothels and bars. According to the United States’ Department of State and media reports, children with diverse sexual orientation and gender identity are also vulnerable to trafficking, a reason being the lack of access to accurate documentation for transgender girls.

Since 2015, a humanitarian crisis has forced 5.4 million Venezuelans to leave their country, and Peru hosts the second largest proportion of Venezuelan migrants after Colombia. Venezuelan children may arrive in Peru irregularly, unaccompanied or undocumented which make them easy targets for traffickers. In search of means of survival, Venezuelan girls are at risk of being trafficked for sexual purposes.

Peru has shown a strong commitment to amending and enacting legislation designed to protect children from sexual exploitation. In particular, it has robust legal provisions in place to protect children from being exploited in prostitution and through child trafficking.

Peru has ratified all major international conventions in the fight against child sexual exploitation and is party to a number of international and regional frameworks. Through membership of the Inter American Children’s Institute they are active in children’s rights, including on this issue. However, limitations still exist in legislation, for example, the legislation protecting children from child marriage and from online sexual exploitation both contain important shortcomings, as discussed below.

Child, early and forced marriage can be considered a prominent problem in Peru, with data from 2020 showing that 14.1% of women between 20 and 24 years old were married or in a cohabiting relationship before the age of 18. Despite this, changes to the Civil Code in 2018 now provide an exemption whereby children over 14 can marry. The score of 0/100 for the Index’s indicator on exemptions to the legal age of marriage reinforces the need for action in this area. Although a 2020 law proposal was submitted with the stated intention of “eradicating adolescent marriages”, it seeks only to reverse the modification of the law from a minimum age of 14 back to 16.

There is also a lack of criminal provisions that prohibit knowingly marrying a child or inducing or forcing a child to marry.

Data from 2020 shows that 69.8% of children aged between 6-11 were using the Internet that year, whilst the corresponding figure was 85.7% for children aged 12-18. Despite the increasingly high access to the Internet for children in Peru, and research indicating that children may be vulnerable to crimes relating to child sexual abuse materials and online grooming, there are still gaps in the legislation. For instance, while child sexual abuse material is well-defined in law, knowingly obtaining access to it is not criminalised.

Additionally, there is no provision that specifically prohibits the live-streaming of child sexual abuse. There are no provisions in the Peruvian legislation that obligate Internet service providers to block, filter or remove child sexual abuse materials from their servers. Although a law proposal that would create such obligations was submitted in 2020, it has not been approved and has faced opposition from COMEX, a business association comprised of companies from different sectors in Peru, including the IT sector. This shortcoming is evidenced by the Index’s score of 0/100 for the indicator for Internet protections.

In Peru, various institutional mechanisms and policies address the sexual exploitation of children, in particular the National Action Plan for Children and Adolescents (2012-2021) and the National Action Plan Against Human Trafficking (2017-2021), which were both renewed until 2030 through the adoption of two new policies in June and July 2021. However, the implementation of these previous plans, despite being well established, were hampered in practice by limited indications of actual coordination between agencies as well as by public data lacking detail and useful disaggregation

To monitor the National Action Plan for Children and Adolescents, a permanent multi-sectoral commission with members from ministries and public bodies was set up to report annually on actions taken to implement this plan, including in the field of combating the sexual exploitation of children. Although this illustrates Peru’s political will to tackle the sexual exploitation of children, the Committee on the Rights of the Child noted in 2016 that limited resources were allocated to this national action plan and that it was unclear how the national and regional authorities cooperate in practice. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that currently, ministries rarely coordinate with each other regarding the topic of the sexual exploitation of children.

In addition, under the law, regional governments must adopt regional action plans to prevent human trafficking, and support people who have faced human trafficking by ensuring the functioning of shelters and their access to healthcare and social services. However, from 2018 to 2019, 76% of regional authorities had not allocated any specific budget to fight human trafficking. NGOs also found that, during the same period, not all regional and local authorities reported all the cases of human trafficking detected in their geographical area to the prosecution office.

The same problem was noted in relation to child sexual exploitation in establishment-based prostitution.

Peru’s response to the sexual exploitation of children is weakened by gaps in the collection and classification of public data on all forms of sexual exploitation of children, including in the online sphere. Data on human trafficking is regularly published by the National Institute of Statistics but its lack of disaggregation does not allow determinations of which cases involve child trafficking for sexual purposes.

Moreover, data gathered annually to monitor the National Action Plan for Children and Adolescents are partial and only covers some aspects of the sexual exploitation of children such as data on investigated cases of child sexual abuse materials or reported cases of child sexual exploitation in prostitution.

The data from the hotline for domestic and sexual violence run by the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Populations (100) shows that, from January to June 2021, 31,198 calls involved a child and 6,081 calls related to sexual offences, but it is not possible from the data to specify how many related to sexual offences against children. Peru scored 23/100 for the indicator related to data collection in the Index.

The collection of consistent, disaggregated and categorised data on sexual exploitation of children would help to assess the scale of these crimes and children’s access to justice and existing services, as well as to design policies addressing the actual needs of those children.

The introduction of the Code of Conduct against Sexual Exploitation of Children and Adolescents in Travel and Tourism in 2018 is a standout example of strong action to engage industry in the fight against child sexual exploitation. As of 2020, 8,710 Peruvian tourism establishments have signed this Code of Conduct and are obliged to report annually on their cooperation with it.

In contrast, media industry engagement received a score of 0/100 in the related Index indicator, as there are currently no guidelines for media and journalists to report on crimes related to sexual exploitation of children.

Civil society organisations in Peru are active in fighting sexual exploitation of children and there are numerous examples of good practice. For instance, In June 2021, CHS Alternativo launched the campaign “Navego Tranqui” (Navigate Safely) focused on preventing online child sexual exploitation which reached from 16,000 to 24,000 people by September 2021. Not every adult and child is online, so materials like posters and signs in strategic public spaces and public transportation, also spread the messages about online child sexual exploitation and how to report it. The project also seeks to gather relevant data on this crime.

Additionally, in May 2021 the Ministry of Women and Vulnerable Population cooperated with multiple NGOs in the project “Connectate sin Riesgo” (Log In Without Risk) that aimed to raise awareness of online crimes such as sexual extortion and online grooming.

Whilst NGOs have engaged children in programmes relating to sexual exploitation, the government shares the responsibility in this endeavour, a sentiment echoed by the Committee on the Rights of the Child in its concluding observations on Peru in 2016. Lastly, the government could engage more with civil society organisations to implement community-based awareness raising initiatives within Indigenous and rural communities, in particular through including comprehensive sexuality education based on a gender and culturally-sensitive approaches to preventing sexual violence.