ECPAT International and TACTEENNAEIL partnered to complete research on the sexual exploitation of South Korean boys during 2021. The research reveals gaps between recently updated laws and people’s knowledge, harmful gender stereotypes, and limited confidence in working with boys among frontline workers.

As part of ECPAT’s Global Boys Initiative, the South Korea Report is the second of ten country reports to be released that deeply explore the sexual exploitation of boys – an issue too long ignored. The Global Boys Initiative aims to improve global knowledge and inform efforts to protect boys and gender diverse children from being sexually exploited.

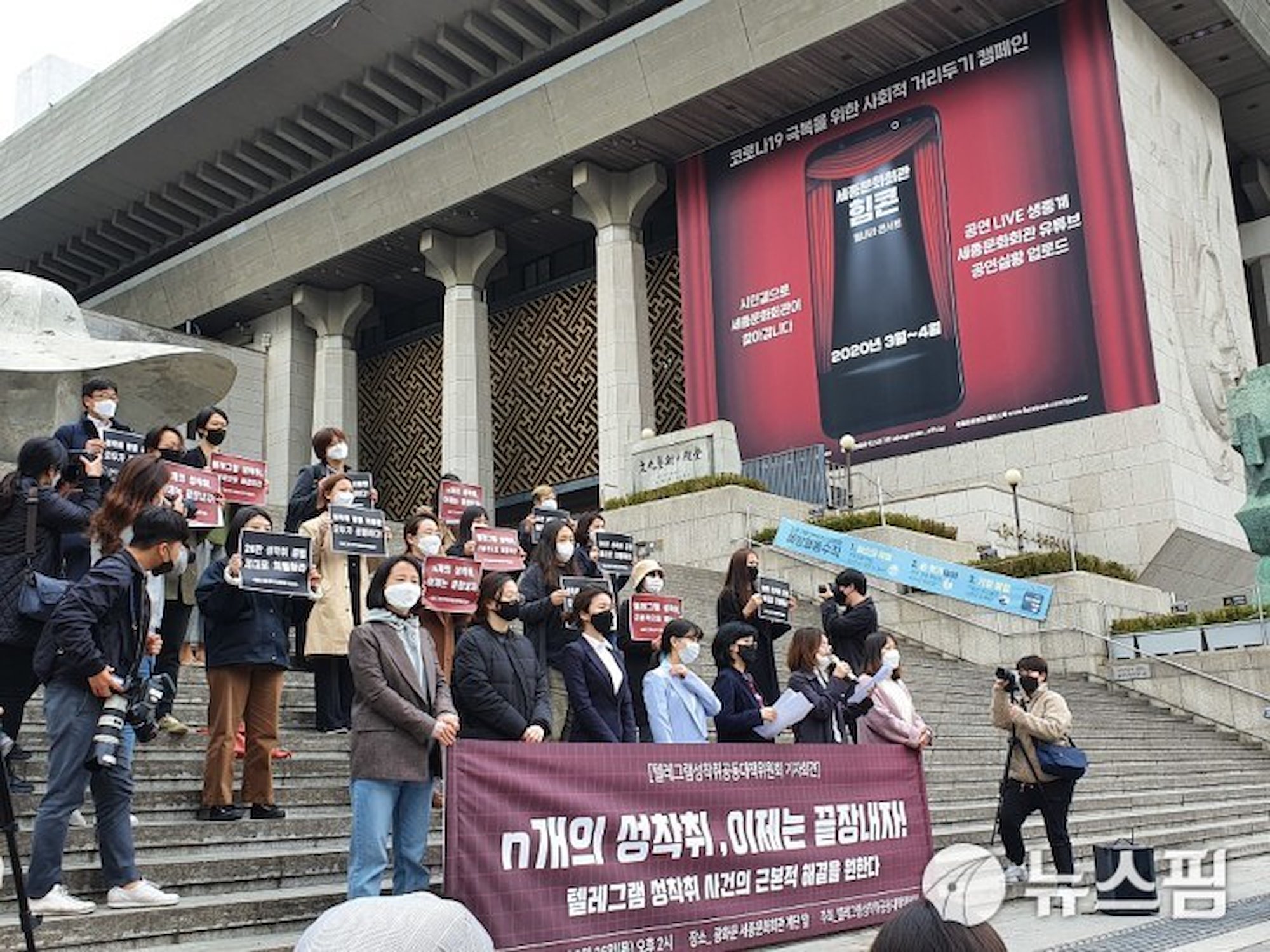

South Korea has shown a strong commitment to protect all children from sexual exploitation by adopting several international children’s rights instruments, and recent revisions to laws have made them gender inclusive – recognising male sexual victimization. High-profile stories involving online child sexual exploitation such as the ‘Nth Room’ case in 2020 have attracted national attention and highlighted that boys too can be victims of sexual violence. But the reality is that gender norms about boys persist, and can make accessing help very difficult for them.

To better understand what puts South Korean boys at risk and why they may not be receiving the support they need, the ECPAT research undertook conversations with boys who had experienced sexual exploitation, a survey of 56 frontline social support workers and analysis of South Korea’s laws related to child sexual exploitation.

“Boys are strong, not vulnerable, and able to protect themselves”

~ Male frontline worker

A common attitude reported by both frontline workers and boys was that the public don’t perceive boys to be vulnerable to sexual exploitation. This in turn leads to stigma and shame when boys are victims, as they feel they somehow failed, or are even at fault when they are abused by adult offenders. Notably, the boys who took part in our research indicated that frontline workers sometimes assumed that boys were not as seriously affected as girls might be by sexual exploitation, or that they could recover more quickly. There was a general belief that child sexual exploitation was not as serious for boys as it is for girls.

“People think that when it happens to boys, it’s just like a punch in the face, nothing serious. They think that a boy will recover quickly.”

~ Sunhye Kang, researcher coordinator at TACTEENNAEIL/ECPAT Korea

Our research indicated that boys were most likely to be sexually exploited by male offenders, often who were in positions of power and authority – but as many as 17% of the cases that workers reflected on were estimated to involve female offenders. Support workers also estimated that a majority of offenders are South Korean nationals.

“I don’t know why they didn’t notice it… definitely, something was wrong with me.”

~ Male research participant

In our research, the boys we spoke with explained how it took them a long time to build up the courage to disclose their experiences. Reasons included fears that they would be blamed for what happened, confusion and uncertainty about whether what happened was wrong, not knowing who to tell – as well as concerns that they might face rejection from their family. One boy described his fears that if he disclosed the abuse, he could be in trouble with the police.

However, even though they didn’t directly disclose, the boys recalled changes in their own behaviour after the abuse. They described things like skipping school, drinking or smoking, things that they hoped trusted adults would notice and reach out to offer support.

The boys’ reflections contrasted with the responses from frontline workers who commonly said that they assumed boys did not wish to talk about their experiences with helpers. This disconnection between boys and workers needs unscrambling – so boys may access the help and support they need.

In June 2021, a 26-year-old Korean man was arrested after grooming boys on social media and disseminating nearly 7000 child sexual abuse materials online. The perpetrator pretended to be a woman, and used more than 30 social media accounts, coercing boys to send him naked images and videos. He also assaulted and raped boys during in-person contact. Online child sexual exploitation is an increasingly widespread issue in Korea, putting boys at increased risk too.

One boy we interviewed had been contacted and groomed online and subsequently abused offline, citing that he did not seek help due to not being aware that what happened to him was abuse or exploitation at first, and worrying that others would think he had ‘consented’ to what had happened. He assumed that if he did disclose, that he would be in trouble with the police.

In addition, boys explained that at school, whilst they learned about puberty and sexuality, they did not learn about sexual exploitation or abuse, and what to do or who to talk to if it happens. Similarly, key barriers to disclosure of abuse perceived by service providers included:

Social norms that perpetrate the silencing of boys, combined with a history of bullying and sexual violence in Korean schools leaves room for offenders to take advantage of the situation and get away with their crimes.

Support workers’ opinions on the quality and availability of existing support services were overall low-to-moderate. When it came to reintegration services particularly, more than a third (36%) of frontline workers rated their quality as “poor”, whilst a staggering 46% rated their availability as “poor”.

Suggestions to overcome such quality constraints were made by frontline workers:

“We need to educate the people on severity of the damage regardless of gender when it comes to damages from sexual violence.”

~ Male frontline worker

Overall, South Korea has shown a strong commitment to protecting children from sexual exploitation – evident through their ratification of numerous international instruments, and continued efforts to improve relevant laws:

However, the changes in laws are not yet common knowledge, and the fear of being criminalised is still preventing boys from seeking help. While South Korean legislation now provides equal protection for boys and girls subjected to sexual exploitation the evidence suggests that boys make up a small fraction of victims accessing justice and support.

There are also still some legal loopholes which offenders can take advantage of, which continue to put children of all genders at risk. These include:

The South Korea Report concludes with detailed recommendations:

Read: Boys in Thailand would stop selling sex if they could

About ECPAT’s Global Boys Initiative

Comment, like and share to help us get the word out! #ECPATBoysStudy

Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | Linkedin