Both Interpol and Europol confirm that child sexual abuse material is increasingly distributed through social media messaging apps, also in the wake of COVID-19. Since 2019, South Korea has been battling a particularly complex case of online child sexual exploitation—a network of chat rooms called ‘Nth rooms’. Each of the rooms was exclusive messaging groups where users produced and traded child sexual abuse material, often obtained through blackmailing women and children. The case gained extensive media attention and sparked outrage among people, but this is likely just the tip of the iceberg.

South Korea is known to be a leader in the internet industry with universal internet access and some of the fastest internet speeds in the world. According to research cited in ECPAT’s Country Overview Report on South Korea in 2017, 100% of children in the country have access to the internet, and 60.8% of children under nine are using smartphones. However, because the internet makes it easier for offenders to produce, access and share child sexual abuse material, children are facing a greater risk of danger while they spend more time online.

The leader of the ‘Nth rooms’ posed as a police officer to target victims and blackmail them into sending photos

In early 2019, reports of chat rooms sharing online child sex abuse material hosted on the messaging app Telegram began to surface in South Korea. They said the leader and organiser of the ‘Nth rooms’ would reportedly pose as a police officer to target minors and blackmail them into sending photos and videos, which were then uploaded and shared with other ‘Nth room’ members. These rooms became increasingly popular and eventually developed into an underground network for offenders seeking content.

While the ‘Nth room’ was operating, a similar chat room began to evolve. One room, in particular, known as the ‘Baksa room’, would charge users fees in cryptocurrency to enter the chat rooms. Depending on the amount of the payment, users were allowed to request their own ‘exclusive’ content. Leaders of the network used similar ‘Nth room’ methods of blackmailing victims into creating new images and videos of abuse. By posting false model and escort job opportunities, perpetrators targeted women and young girls. After obtaining their personal information, they threatened to release their photos and videos if they did not comply with the demands.

‘Baksa room’ members were ranked and divided based on how much they paid, with some of the most abusive material purchased at high prices. VIP members, those who had paid higher fees, were given access to more on-demand, horrifyingly ‘exclusive’ material depicting the sexual abuse of children. Some VIPs even had the option of watching their victims get ‘branded’ with the offenders’ names in the videos they had purchased. Reports say that ‘Baksa room’ users were paying up to KRW 1,500,000 (roughly USD 1,260) for access.

VIP users would pay up to USD 1,260 to access horrifying ‘exclusive’ abusive content.

Following the arrest of the ‘Baksa room’ leader in March 2020, a ‘Cybercrime investigation unit task force’ was formed in South Korea. They announced a plan to thoroughly investigate other major online child sex abuse networks on the dark web and messaging apps.

ECPAT’s research with law enforcement experts has shown that techniques for generating and sharing child sexual abuse material tend to adapt to developments in technology. Interviewees reported that it is often difficult to identify offenders and victims, as many online platforms preserve user anonymity. This is especially difficult in the case of the ‘Baksa room’, where payments for these materials were made in cryptocurrency, making users challenging to trace.

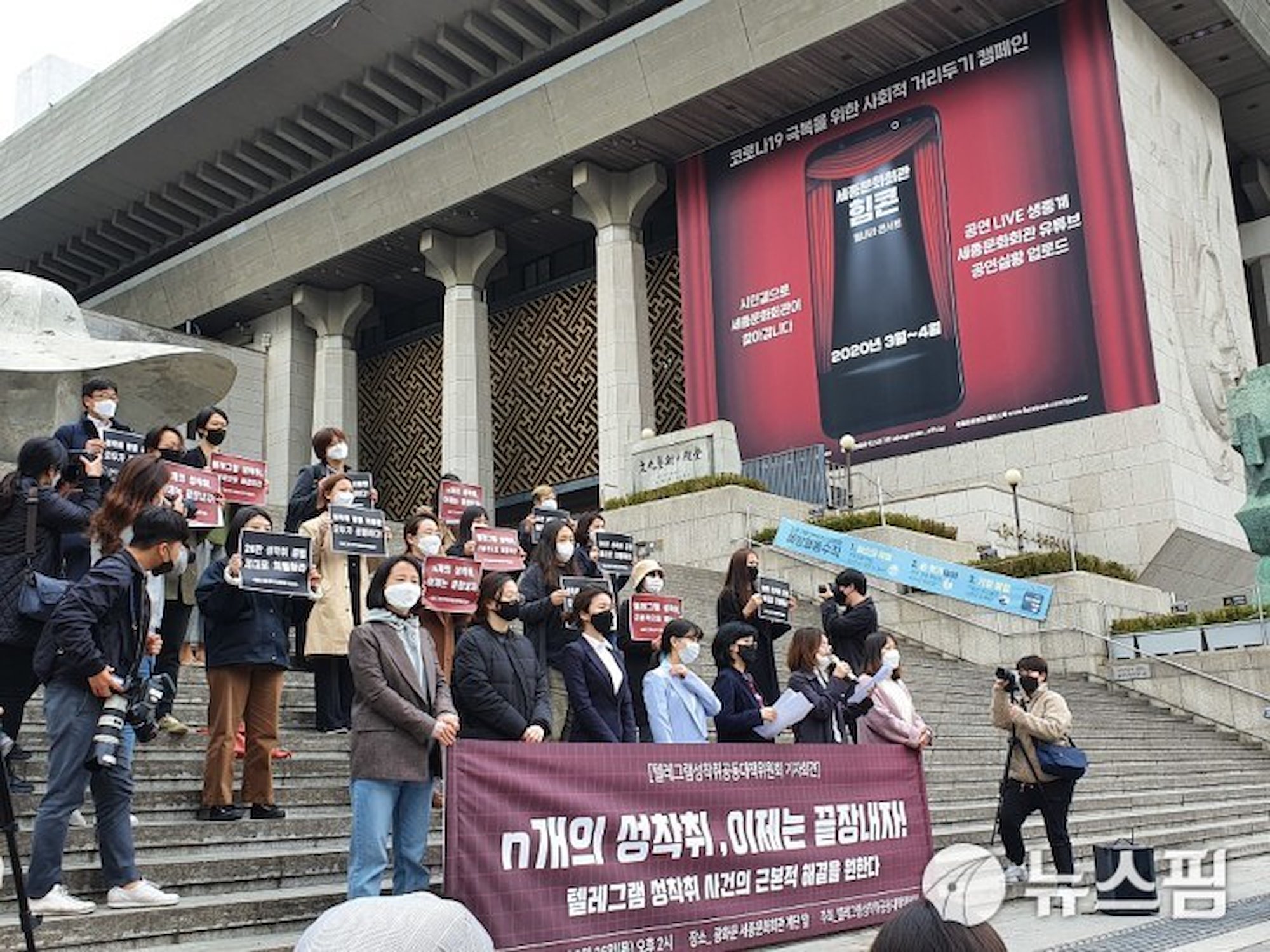

Demonstrators in South Korea. Photo: ECPAT Korea

The arrests of chat room leaders and dismantling the ‘Nth room’ network is likely to push user demand elsewhere, and offenders are known to use any means necessary to access or distribute child sexual abuse material. Technology constantly evolves, and in response, online child sex offenders adapt. As laws get stronger in one country, offenders may turn their attention to another state where laws are more lenient.

The production and exchange of child sexual abuse material started to transform around 2012 when the dark web started to be widely used for all kinds of illegal activities. Many offenders have gradually moved from the surface web and to the dark web to gain anonymity. In forums, they create a space dedicated to the production and exchange of child sexual abuse material, tips and advice about online grooming and how to travel to exploit children safely.

Concerned by the ‘Nth rooms’ case, ECPAT Korea has been working to raise more public and government awareness. Along with several other organisations, they created an NGO union to lobby for greater government action and stronger legal definitions for child sexual exploitation crimes.

Online child sex abuse materials have become an international threat. Each nation’s investigation unit must work together, and countries should embrace other countries’ most effective measures against this crime.

—Sunhye Kang, Manager, ECPAT Korea

The union conducted a survey asking how the public views current legislation on child sex abuse material. The surveys received favourable support for addressing the issue and sparked a public petition that placed pressure on the government to amend their existing laws. In April 2020, the legal age of consent was raised from 13 to 16. In the same month, the ‘Telecommunications Business Act’ was revised in response to the ‘Nth room’ case, requiring online platforms to remove any digital content involving sexual crimes, including child sex abuse material.

Promotional material for ECPAT Korea’s national conference on ending online child sexual exploitation

In addition to advocating for legal change, ECPAT Korea also worked to support child victims of online child sexual abuse, and they set up a fundraiser through the popular messaging app, KakaoTalk. Money raised from the campaign will go to efforts teaching victims more about sexual rights, as well as treatment programs and financial support for children in need.

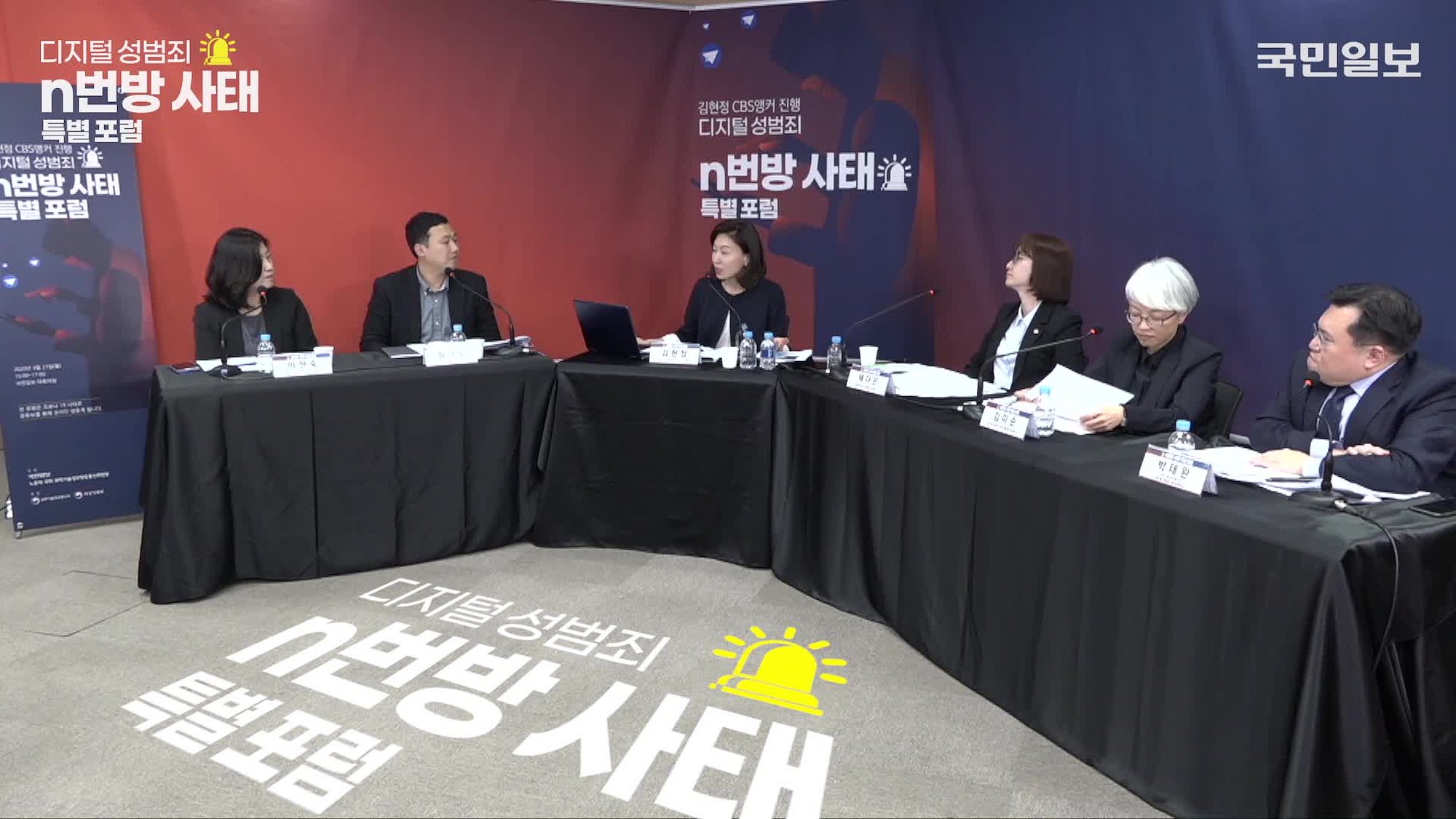

A special forum held to discuss the Nth room case, with ECPAT Korea in participation. Photo: ECPAT Korea

Though the ‘Nth room’ case may only be the tip of the iceberg, the issue of online child sexual abuse material in South Korea has raised serious concerns in other countries, such as neighbouring Taiwan. After learning of the South Korean case, information from a public survey in Taiwan has revealed support for heavier penalties to be imposed for possession of images involving the sexual exploitation of children. In response, ECPAT Taiwan began to advocate this issue with lawmakers in the country, in the same spirit as ECPAT Korea had done with its government. They are working on a proposal that criminalises the possession of child sex abuse material and strengthens punishment to a minimum term of imprisonment of at least one year.

We must adopt stricter laws to punish the production, distribution, and possession of child sexual abuse material to prevent more harm.

-ECPAT Taiwan

The benefit of a high-profile case such as the ‘Nth room’ one is the public debate and political attention. In this case, it allowed our members to work alongside lawmakers to strengthen children’s protection against sexual abuse and exploitation in their countries. But we also need to face reality. And the truth is that we already know new ‘Nth rooms’ and ‘Baksa rooms’ are operating both in South Korea and Taiwan, and in the rest of the world. Knowing this, we cannot continue to await new cases causing outrage before we take further action.

E-privacy is on top of both public and political debate, and while strong encryption plays a valuable role in keeping citizens and their data safe, it also poses a threat to children’s online safety and the possibilities of investigating cases. Earlier this year, Facebook announced they are encrypting Messenger. When doing so they are aggravating law enforcement investigations to identify child victims and stop ongoing situations of sexual abuse. On December 21, 2020, an e-Privacy law in the European Union will make it illegal for tech companies to use technology to detect online child sexual abuse and exploitation material unless the Parliament approves an “interim regulation”. This exception to the law could prevent a global catastrophe by allowing tech companies to continue to use the tools needed to protect and rescue children.

These two examples are by no means suggested to enable child sexual abuse and exploitation, and the tools used pose no threat at all to anybody’s privacy., except for children’s. That is why tech companies as well as law- and policymakers need to rethink their strategy in order to be able to fight the spread of child sexual abuse material online.