From the household surveys conducted, 81% of children aged between 12-17 were internet users, primarily using the internet for schoolwork, social media, and chatting online.

Although 82% of interviewed children believe that they could make the right decisions when faced with risky online situations, 47% have never received any formal information regarding their online safety.

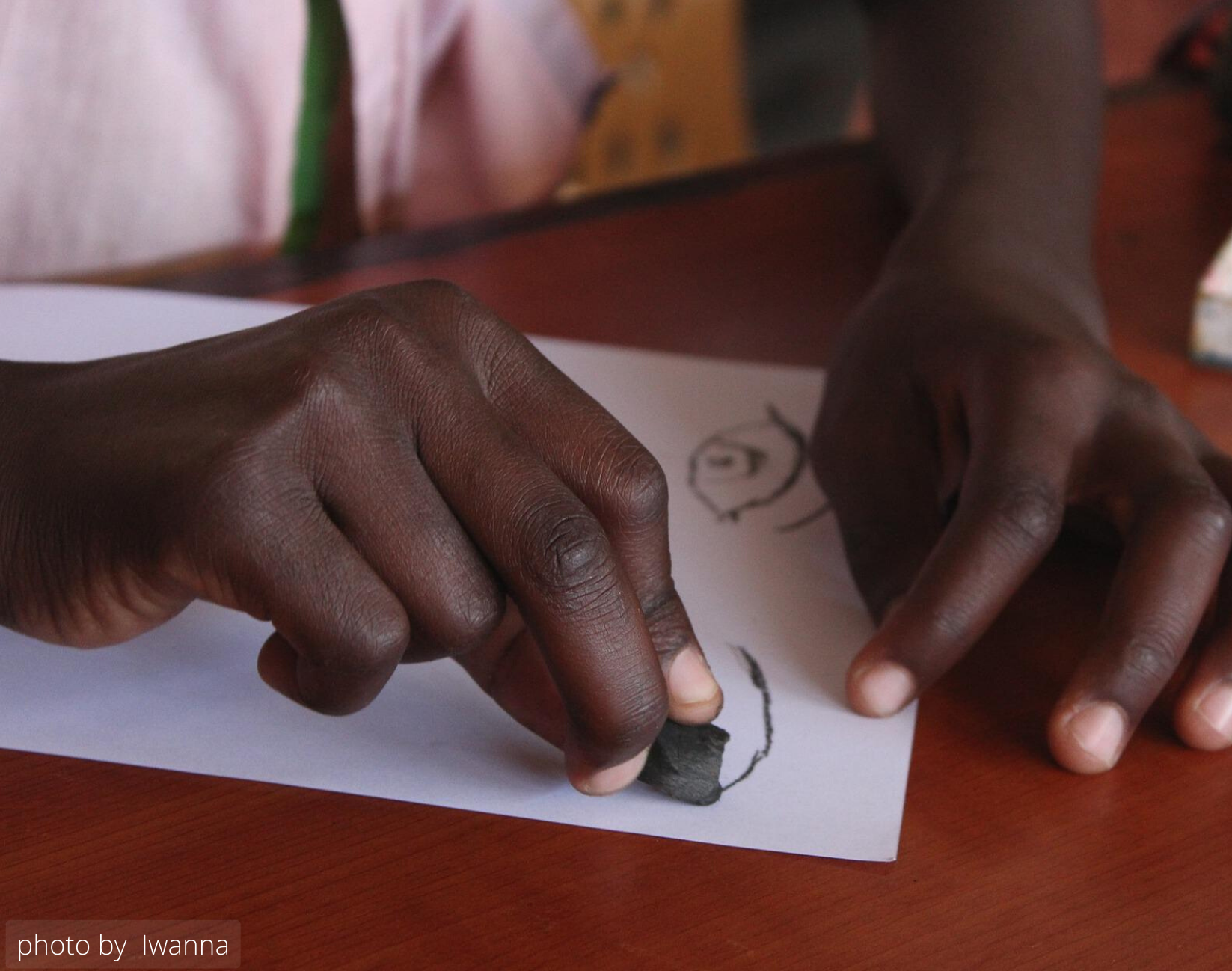

Conversations with young survivors indicated that they want to learn how to stay safe online, rather than just receive messages about online dangers:

“[If I was a parent], I would remind my child if they were engaging in games or whatever, to be careful. I will tell them if you want to open a Facebook account, it must be done at a certain age when the child can understand the risks that are there, not while they are still young, because it can influence their minds. When they are old enough to be on the internet, I will walk them through the process, make it fun and allow them to explore.”

Despite the rise in cases of online child sexual exploitation and abuse, caregivers had a low level of awareness of the crime, typically relying on radio, television, friends and family, or their child’s school for information on how to support their children’s internet use and keep them safe online.

“Parents have no clue what their kids are doing on the Internet, and they have no clue of the dangers.”

~ representative from the Office of the Prosecutor

A lack of awareness not only limits the role caregivers can play in preventing and responding to such crimes, but it can also lead to low levels of disclosure among children impacted by online sexual exploitation and abuse. Educating caregivers to provide them with the tools to assist in keeping their children safe online is crucial to success.

The household survey found that around 9% of internet-using children surveyed in Namibia were subjected to clear instances of online sexual exploitation and abuse in the past year:

Children were also subjected to other harmful experiences online:

Social media platforms and messaging applications were predominantly where children experienced this—namely Facebook, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram.

The majority of offences (80%) were committed by someone the child already knew—including family members and adult friends.

Only one in four instances were found to be someone unknown to the child.

While most awareness-raising campaigns in Namibia emphasise that children should be wary of ‘dangerous strangers online’, children also need to be aware of the boundaries of what adults and others around them can and cannot do.

Around 30% of children who were subjected to abuse online did not disclose their experiences to anyone. Fear of getting in trouble, the belief that the issues were not serious enough to warrant help, and a lack of awareness about reporting mechanisms were all cited as reasons for the children opting not to report these crimes.

When a survivor from Namibia was asked whether she had disclosed what had happened to her, she shared:

“No, I did not because I was afraid because my mom had warned me not to communicate with people that I do not know on social media, so I was afraid that she will criticise me for doing that.”

When children did open up about their experiences, it was usually to people from their circle of trust—such as friends, siblings. Only 2-6% reported their experiences to formal reporting mechanisms such as the police, social workers, or a helpline.

Data from the report suggests that public awareness campaigns and reporting mechanisms need to be adapted to better reflect the experiences of children in Namibia.

Some recommendations outlined in this report include:

The Disrupting Harm initiative is a multi-country research project aimed at understanding the context, threats, as well as children’s perspectives of online child sexual exploitation and abuse across 13 countries in Eastern and Southern Africa and Southeast Asia. Funded by the Global Partnership to End Violence Against Children, through its Safe Online initiative, this large-scale research project draws on the expertise of ECPAT International, INTERPOL, UNICEF Office of Research – Innocenti and their networks of partners.

The following research activities were conducted as part of this report:

Read the full report in English

About Disrupting Harm, our research, and our partners

Comment, like and share to help us get the word out! #DisruptingHarm

Twitter | Facebook | Instagram | LinkedIn